Today’s sponsor is Fintool. Fintool is an AI copilot tailored for institutional investors. Frankly, it’s amazing at comparing earnings transcripts and finding key quotes. One of my favorite things is that it links to the source documents and highlights the specific quote so you can verify everything. It has saved me and institutional investors like Kennedy Capital or First Manhattan a lot of time. It also has a qualitative screener that is quite interesting.

Carvana is a well-known, highly controversial company. The felony charges against the founder’s father, high debt load, capital intensity, near bankruptcy experience, and infamously volatile stock are all ingredients for vocal bulls and bears. With that said, let’s break down the business.

Carvana is the “Amazon of used cars”. You can literally order a car from your couch and it will show up in your driveway in a week or so. Select markets actually offer same day delivery for an extra fee. And then, of course, if you’re nearby, you can skip the delivery fee and pick your car up from one of the famous vending machines.

Everyone knows the used car buying experience is terrible. The phrase “used car salesman”, itself, is used derogatorily. CarMax was the first to offer a no-haggling experience all the way back in 1993 but Carvana was the first to truly make the experience internet native. Carvana was spun out of DriveTime in 2013 by Ernie Garcia III, the son of Ernie Garcia II. Garcia II pleaded guilty in 1990 to charges of bank fraud in the Lincoln Savings and Loan debacle. He was sentenced to three years on probation. Shortly after this, Garcia II bought a rental car franchise called Ugly Duckling and turned it eventually into DriveTime, a used car dealership network that specializes in subprime customers. But Ernie Garcia III is not his father. As the Bible says in Jeremiah 31:29-30 “In those days they shall no longer say: ‘The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children's teeth are set on edge.’ But everyone shall die for his own sin. Each man who eats sour grapes, his teeth shall be set on edge.” This verse is saying that everyone is responsible for their own actions. The idea that children would be punished for their father’s sins was only for a moment in God’s redemptive history. Sure, our familial patterns tend to repeat but each of us can only control our own behaviors. I only belabor this point because I see it thrown at Garcia III quite often. But he’s his own person. Move on.

Garcia III went to Stanford and is a highly dynamic leader. If you listen to all of the past earnings calls, you can feel his enthusiasm and passion for the business. Those things don’t show up in the financials but they can be very important. Garcia III owns about 30 million shares which is almost 14% of outstanding shares. His dad owns 45 million shares which is about 20% so collectively, they own more than one-third of the business. However, they have roughly 85% voting control because of super-voting B shares. This is quite common for high ownership, founder-led companies but I understand why it makes a lot of folks nervous. On the other hand, a founder’s worst nightmare besides bankruptcy is getting their business taken away from them.

I think the background of the Garcia’s is particularly important because of how much capital they had to put into this business. Without DriveTime and Garcia II, Carvana very likely wouldn't have made it where they are today. The combination of strong financial backing coupled with a ZIRP environment allowed the company to build a moat which will be quite difficult to replicate.

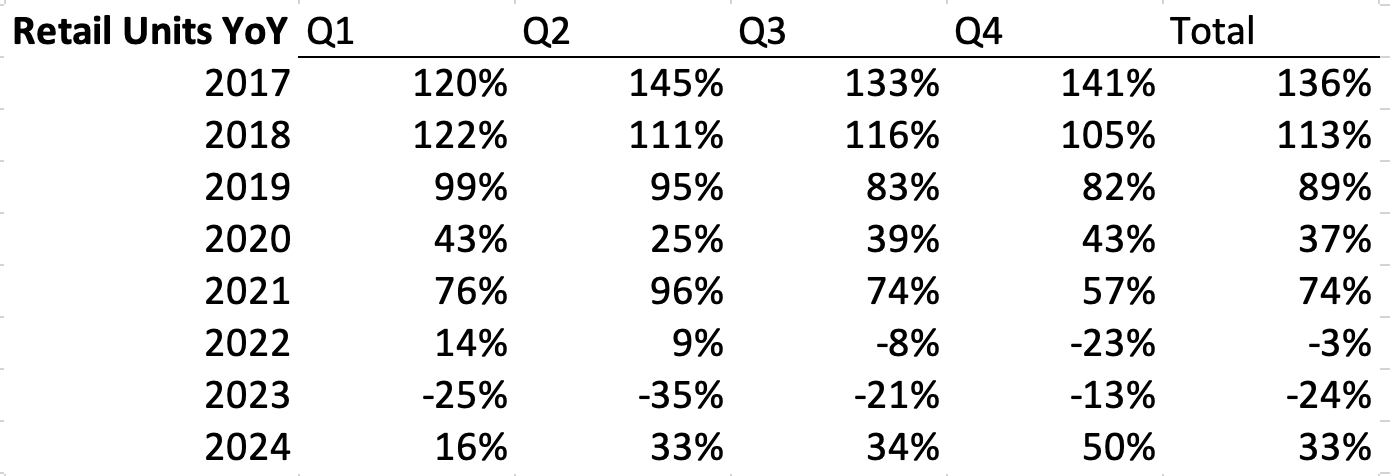

Last year, the company sold a touch over 416,000 used cars at an average price of ~$23,000. The US used car market sees 36 million cars change hands every year so Carvana is just over 1% penetrated. Here are the retail growth rates since IPO, growing more than 20-fold since 2016.

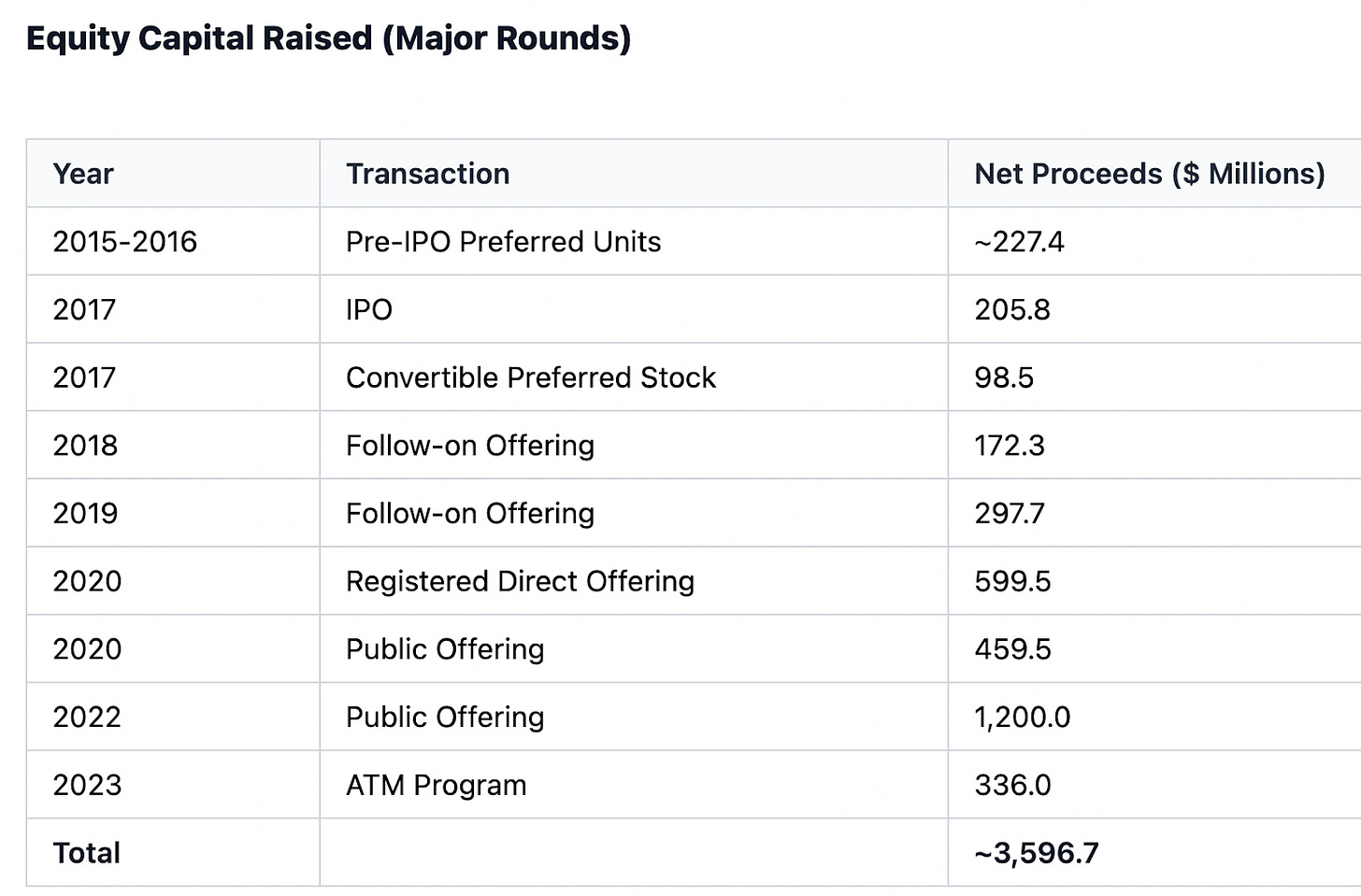

This type of growth doesn’t typically happen when there is no value prop. Bears will say it's because they were selling dollars for 90 cents and bulls will say they were busy building a moat and the cash came later. And a moat they did build. The company spent roughly $10 billion over 10 years to build 18 inspection and reconditioning centers, 32 vending machines, more than 1,000 specialized delivery trucks, and 56 auction sites from its ADESA acquisition in 2022. Those assets are not easy to replicate and they were a result of a unique founding story and very cheap money. I’ve listed all of the equity and debt transactions for the company (using today’s sponsor) which is roughly $10 billion.

The company currently has operational capacity for 1 million vehicles and the real estate footprint for 3 million vehicles. At 3 million vehicles, they’d have 8% market share in the US and retail revenue would be roughly $70 billion. At the current 10% adjusted EBITDA margins, that’s $7 billion in EBITDA versus today’s enterprise value of $49 billion. I’m not sure how long that would take but you can run the numbers yourself with different timeframes and multiples. In a decade and 20x EBITDA, you get about an 11% return but that’s ignoring any cash build so the IRR would be a bit higher. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, we haven’t even broken down the granular economics yet.

For 2024, the company did $13.7 billion in revenue. That was composed of $9.7 billion in used car revenue that doesn’t include financing, $2.8 billion in wholesale revenue from cars that don’t meet Carvana’s standards for retail sales, and about $1.2 billion from “other” revenue which mainly consists of financing gain on sales.

When you divide $9.7 billion by 416,000 units, you get ~$23,300. On the wholesale front, Carvana facilitated about 200,000 units for an average price of ~$9,500. And then after the ADESA acquisition, they also enable third-party sellers to use their wholesale marketplace. They sold about 955,000 units last year for roughly $900 million. Basically, you can think of the wholesale marketplace as having a 10% take-rate for providing the auction services and holding the inventory. A lot of the wholesale and retail volume, not on the marketplace, is sourced from customer trade-ins. This group is not as sophisticated as career dealership buyers so the margins are typically a bit better, though the inbound transportation costs that hit COGS offset that benefit a little bit. You can clearly see that these cars aren’t in the greatest shape. And lastly, Carvana made roughly $2,800 per car in revenue in financing and other products like vehicle services contracts and guaranteed asset protection plans.

The way a car dealership makes money is typically very little margin on the metal (the actual car) and then real money makers are in financing (mainly) and service contracts. If you look at the gross profit per unit, Carvana made about $3,300 per car which comes out to a 14% gross margin on the metal. Wholesale gross margins are 10% as dealers/the company just wants to get rid of low quality inventory. The wholesale marketplace does about 16% gross margins but you’d think that would be higher. A good chunk is depreciation from the 6,500 acres of land that came from ADESA to auction and store the cars. Further, Carvana has also started reconditioning third-party inventory that gets placed in this revenue line so it’s not really a true marketplace, even though I earlier said it’s easy to think about a 10% take-rate. It is just simpler to think of it that way since it’s not a crucial part of the business at 6% of total revenue.

But the “other” revenue is essentially 100% gross margin. So even though “other” revenue is about 9% of total sales, it accounts for 40% of gross profit per unit. Using another framing, it’s even more drastic. The average retail car on Carvana sells to a car buyer for $23,300 – we’ve established that. After accounting for picking up the car and reconditioning costs, Carvana does about $3,300 in gross profit. So you can imagine the company buying a 2018 Kia Optima (totally random) for $18,000 on a trade-in, spending $500 hauling that vehicle to a reconditioning center, and then fixing a fuel pump for $1,500 and selling that car for $23,300 to the final customer. That’s roughly how it works, ignoring the depreciation costs for the reconditioning centers. But if you look at the gross profit contribution from “other” as a percentage of just retail units – appropriately stripping out wholesale – then it’s more like 46%. Again, the per unit gross profit for “other” is roughly $2,800 so that’s not far away from the absolute dollar amount of $3,300 on the car itself.

But then the all important question remains – how does this “other” revenue work? Well, it’s a little confusing so bear with me. Car buyers finance about 80% of the time and Carvana’s customer base is no different (lots of people out there don’t listen to Dave Ramsey lol). Carvana does a credit check on these buyers and then gives them a downpayment and monthly payment quote. For subprime borrowers, Carvana requires a higher down payment and charges a higher interest rate. This is just how credit works. Higher risk requires higher reward. Because Carvana does the underwriting themselves, they don’t turn many people down but rather give more stringent terms. Since some people will default, they need to charge high rates to offset the losses. Unfortunately, in a profitable credit business, the responsible payers subsidize those who ultimately can’t pay. Once again, that’s just how it works. After a buyer is approved for financing and maybe they get a vehicle service contract thrown in at a DriveTime location, they will pay the downpayment, receive their car and then, hopefully, keep up with the monthly payment.

Carvana will then take the loans and package them up and sell them to investors. Just like in the mortgage industry, originators don’t want the loans on their balance sheet as it takes too much capital and leaves them holding the bag if their underwriting was poor. At the same time, if your underwriting is poor, investors will find out very quickly and you’ll lose trusted partners. Below, you can see the percentage of loans that Carvana held on their own balance sheet. Last year, it was just 7% and some of that is just a timing issue where Carvana will end up selling the remainder in the future.

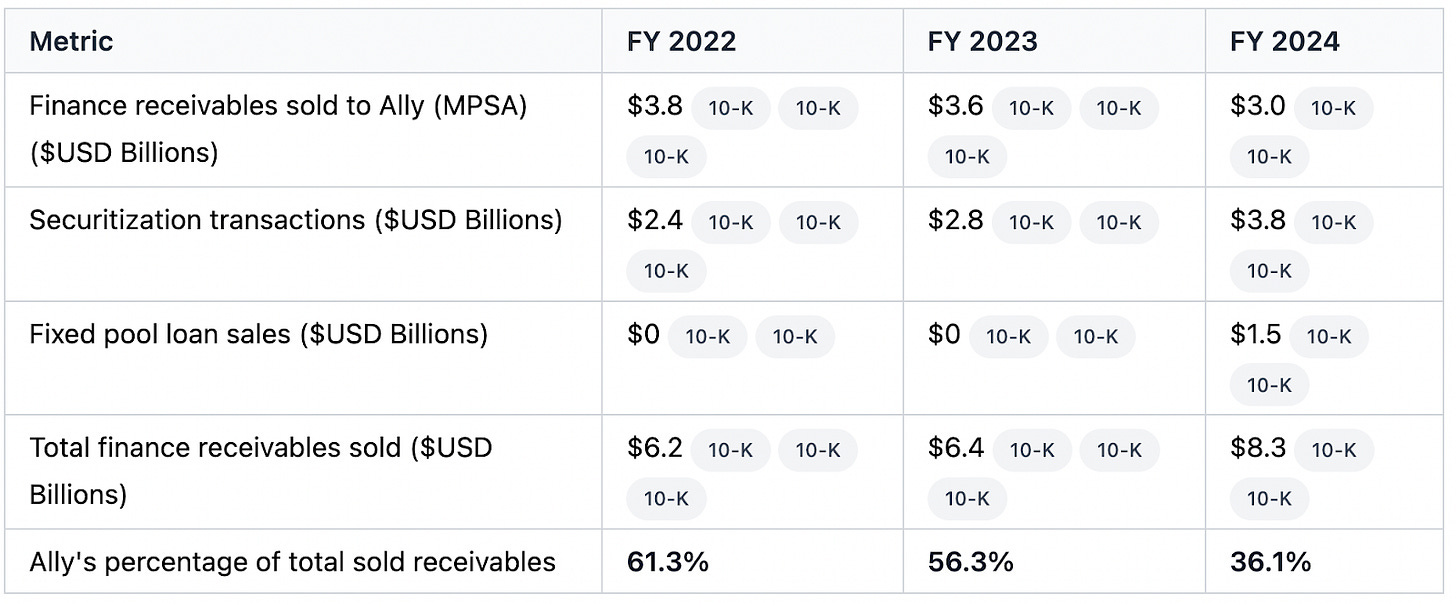

One of Carvana’s most trusted partners is Ally Bank. Below, you can see that Ally used to take the majority of Carvana’s packaged loans. Now, it’s less but still a good chunk. My understanding is that the $1.5 billion in fixed pool loans in 2024 was Cerberus Capital, which is a large credit investor and the Chairman, Dan Quayle, is on Carvana’s board. It’s good news that Ally’s concentration is decreasing. Currently, the agreement between Ally and Carvana is that Ally commits to buying up to $4 billion (capped) per year. Essentially, Carvana has to sell one debt tranche worth $300 million to Ally every quarter. That’s roughly 15,000 cars every 3 months – that’s the minimum and $4 billion per year is the max.

Further, about 65% of “other” revenue is from gain on sales in these asset backed securitizations. You can see that below:

Practically, what this means is that $1,800 per car is from gain on sales of the $2,800 in “other” gross profit per unit. So using our example, Carvana sells the average car for $23,300 and then sells the entire packaged loan for $25,100 to an investor. It might not work perfectly like this since securitizations can include thousands of loans so as to diversify the risk but that’s the basic idea. Carvana, like other car dealers, funds the purchase of their vehicles using a floorplan facility and then once the financing is approved, they put a bunch of their other loans together and sell them in big chunks to investors. These investors, like Ally and Cerberus, make money by paying less than the loans are worth. Maybe the loans are 72 month terms and an 8% APR. Roughly, using an amortization schedule, it’s possible the investor could get paid a total of ~$32,000 in cash from a borrower who doesn’t default. Of course, once again, it isn’t practical to look at a securitization using only one loan since they include thousands but that’s the basic concept of how this all works.

The easy money environment, coupled with Ernie Garcia II’s resources, enabled Carvana to build this vertically integrated platform. But ultimately, Garcia III made it happen. Spending $10 billion over a decade to create an amazing customer experience takes vision and tenacity. The two main competitors, Shift and Vroom filed for bankruptcy during 2023 and 2024, respectively. Now, the only competitor left is Carmax and they don’t really do a full service delivery offering. At one point, Carvana was a money burning company with a growing cohort of competition. Now, after surviving the fire, it makes money and doesn’t have real competition. The company is just over 1% penetrated in their market and they are now experimenting with selling new cars rather than just used ones. This would enable them to be the e-commerce experience for all sorts of car brands. With a unique leader at the helm, a huge market, a deep competitive advantage, Carvana is actually set up pretty well. You do need to understand the credit market because that’s where a good chunk of the profits come from. Relatedly, the company will go through cyclical ups and downs just like the credit market but there is also secular growth since the runway is so long. I wouldn’t get long Carvana into a sharply rising interest rate environment but I do think people shun the company without looking at the first principle fundamentals. My take is this is a special business with a growing moat.

If you enjoyed this, please turn that ♡ into a ♥️. This will help others find this newsletter. Thank you so much 😁

great overview....