Discontinuous Disruption

Here is a taste of a premium post. Along with access to our proprietary research resources, we send out a premium post every Friday. These posts typically center around the companies in our portfolio or cover a more general investing topic like this one.

The year was 2000, the beginning of the tech bubble descent. Still groggy from waking up at 4 am, three men boarded a private plane at the Santa Barbara Airport. Little did they know that the rest of the morning would be a pivotal point in the course of their lives.

Marc Randolph, Barry McCarthy, and the CEO boarded the plane, rented out from Vanna White, the hostess from Wheel of Fortune. They touched down in Dallas a few hours later, excited for the meeting ahead of them.

They had practiced their lines -- they needed this badly. Their company, a fledgling start-up was losing $5 million per year and it looked like it was getting worse. They hoped this meeting would result in an acquisition, a much-needed life-line.

The meeting started and the CEO went through his rehearsed pitch. The listeners, two men, sat silently. After a while, the listeners asked, “how much to buy the company?” The CEO calmly stated, “$50 million.”

Deal’s off. There’s no way. Way too expensive.

Somewhat dejected, the CEO and his two associates headed back to Santa Barbara with only one option: forget about making friends; win.

That CEO is Reed Hastings, the genius behind the media powerhouse, Netflix. The listeners were the CEO and general counsel of the now-bankrupt, Blockbuster.

And there are many similar stories to be told. This is the consequence of a little something called innovation.

A simple definition of innovation is: making improvements. However, there are different kinds. Here are the three we think about often.

1. Sustaining

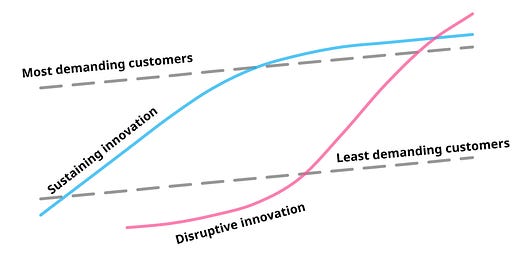

Sustaining innovations are when the same products are made better on common consumer preference vectors (price, capabilities, form factor, etc.). A good example is when Apple releases a new iPhone and it has a higher definition screen and more battery life. These improvements are necessary and a really good sustaining innovation can get you far. The new iPhone now has three cameras, which is awesome for people who have been wanting top-notch picture quality.

2. Discontinuous

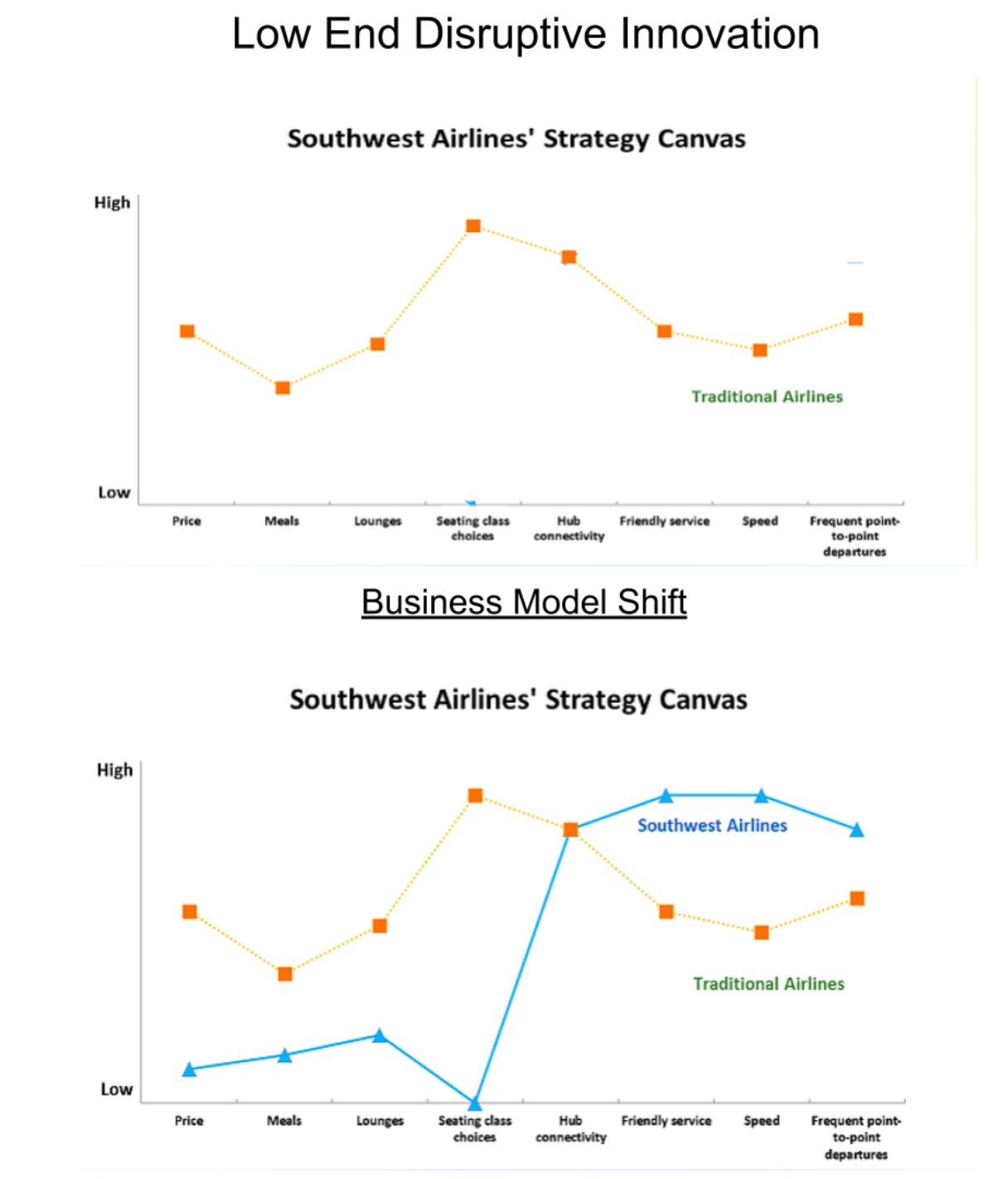

Discontinuous innovations completely change how something is done, typically driven by a platform shift (on-premise to cloud, desktop to mobile, etc.). The shift in platform enables a better customer value proposition on at least one consumer preference vector, which is usually convenience. If it was price, then it would likely fall into the next category.

3. Disruptive

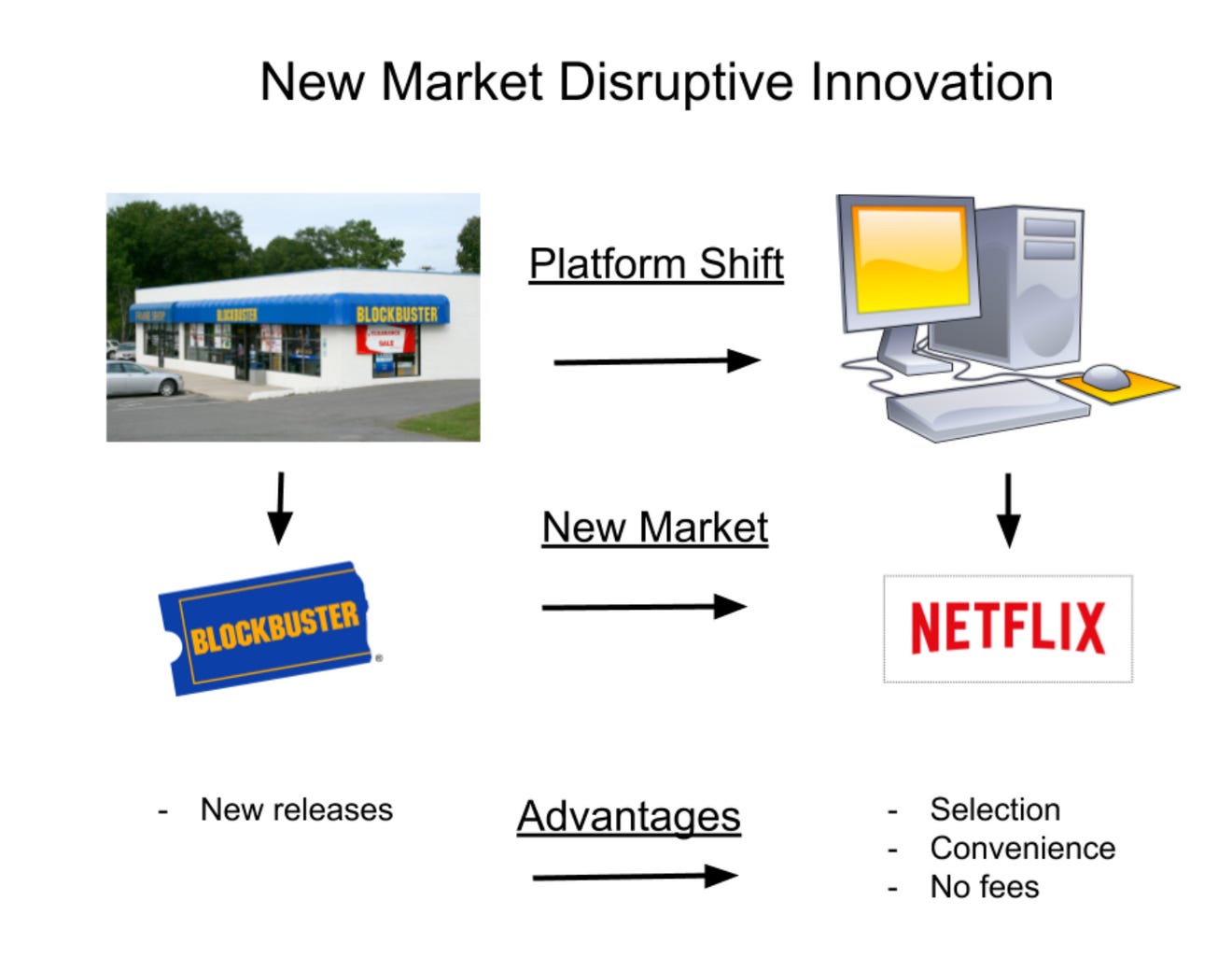

Disruption is when a company either comes in at the low-end of a market or it creates a new market. Contrary to popular usage, disruption does not refer to technology. It is a market orientation that buys time without fierce competition from incumbents.

Here’s our hypothesis: low-end disruptions are typically a result of business model innovation and new-market disruptions are typically a result of platform shifts.

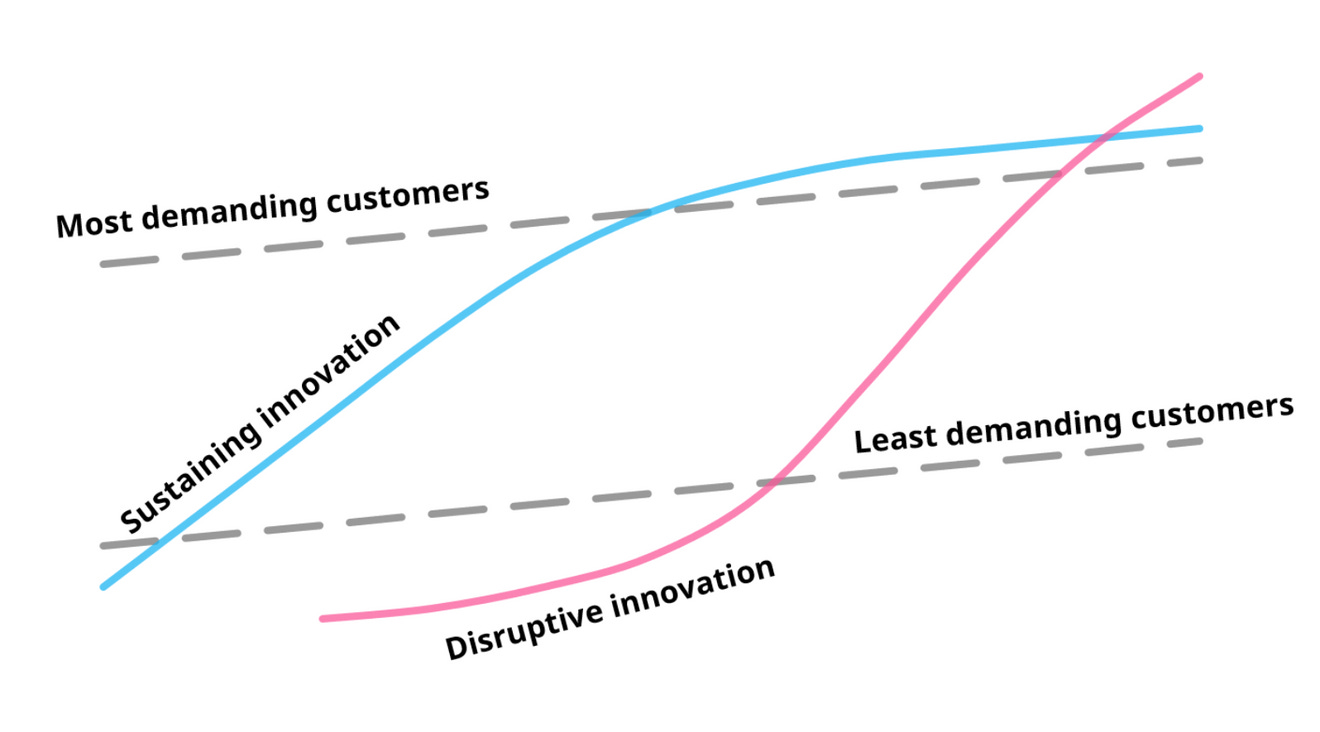

For example, Southwest Airlines changed its business model relative to other airlines. It only bought one type of aircraft to reduce training time and get bigger discounts. It negotiated specific hubs with airports. It removed reserved seating and much more. These business model changes allowed it to enter at the bottom of the market to “disrupt” more traditional carriers.

Netflix is a great example of a new market innovation. When it first started out, it catered to a different type of person, movie buffs who didn’t care about new releases. After all, if you walked into a Blockbuster you could get all the latest movies, right away. On Netflix, though the selection was varied, you had to wait a few days to get your DVDs in the mail. Not until the platform shift from DVDs to streaming, did Netflix really take off. Still, it created a new market and utilized the platform shift. Without the bloated cost structure of Blockbuster, it could effectively disrupt them. As streaming progressed, it could slowly move upmarket to reach more profitable customers. It’s no shock that there are now many more competitors as Netflix has moved slightly up-market. However, the content library it was able to build up from its first-mover advantage, courtesy of disruption, is a moat in itself.

There are many more examples of disruption but the common thread is that they lower price in some form.

With a vastly different business model, a company can start at the low end of the market which requires great execution. Think TJ Maxx or Walmart or Costco. Each of these companies utilized differentiated business models to enter the low end of the market. This is disruptive but not discontinuous. There was no shift in platform.

Differentiating Discontinuous and Disruptive

The idea is that a shift in platforms creates opportunity for discontinuous innovation. For instance, the move to the cloud or the move to the internet are two obvious examples. When platforms change, discontinuous companies emerge.

If a company comes up with a discontinuous innovation, it can go one of two ways. It can be disruptive by starting at the bottom of the market. This is a good idea if the customer acquisition cost (CAC) is small. The smaller the CAC, the better a discontinuous product can disrupt at the bottom of the market. Therefore, it’s not a surprise that many software companies are pushing the freemium model. It’s impossible to disrupt “free.” This drives down the CAC and allows them to up-sell to a large number of customers, eventually providing enough firepower to move upstream.

On the other hand, a company can go immediately to the top of the market. This makes sense if its marginal cost of adding a new customer is high. After all, these highly profitable customers provide companies the necessary money to survive. Of course, there are exceptions to this framework. Uber started at the high end of the market with a black car service and moved down-market, even though its CAC wasn’t extremely high. This seems to make sense with network-driven businesses though because they need to survive long enough to create a critical mass of supply and demand.

However, starting at the high end of the market will likely be a slog. Look at Uber. Right from the beginning, it received immense backlash from taxi companies. That’s because disruption is not a technological breakthrough, it’s a structural advantage that buys time for an upstart to eventually beat an incumbent. One more point on entering the high end of the market with a discontinuous innovation; it’s important to think about switching costs. Uber became a giant company on the back of a discontinuous platform shift but it entered the high end of the market and its product doesn’t have a huge switching cost. Simply download Lyft’s app, scan your credit card and you’re good to go. The problem with attacking the high end of the market is that it attracts competition because that is where the profitable customers are. Without switching costs, it could turn into a price war. That’s the power of disruption.