Today’s sponsor is Fintool. Fintool is an AI copilot tailored for institutional investors. Frankly, it’s amazing at comparing earnings transcripts and finding key quotes. One of my favorite things is that it links to the source documents and highlights the specific quote so you can verify everything. It has saved me and institutional investors like Kennedy Capital or First Manhattan a lot of time. It also has a qualitative screener that is quite interesting.

At its core, FICO helps lenders deal with risk. Founded in 1956 by Bill Fair and Earl Isaac (Fair Isaac Co), the company created a proprietary way for banks to assess how risky it was to lend to someone. And the FICO score was born. Besides these scores, which are bundled and sold to banks and financial institutions, FICO also offers pre-configured decision management applications, consulting services, and a platform-as-a-service for lenders. In case your eyes glazed over at that last sentence, they basically do other software-y stuff besides the scores (which are actually algorithms themselves).

Essentially FICO is a data science company that creates solutions to help lenders make good decisions.

Moat

FICO serves all 100 of the largest banks in the world. This is the key. Banks and other lenders base a lot of their decisions on FICO’s score. This gives FICO leverage because banks are wary of new scoring systems. If a competitor comes in with a new way to assess risk, even at a much lower price, the risk to switch is higher than the reward. This is the essence of why VantageScore, a direct competitor created by the credit bureaus, hasn’t done very well.

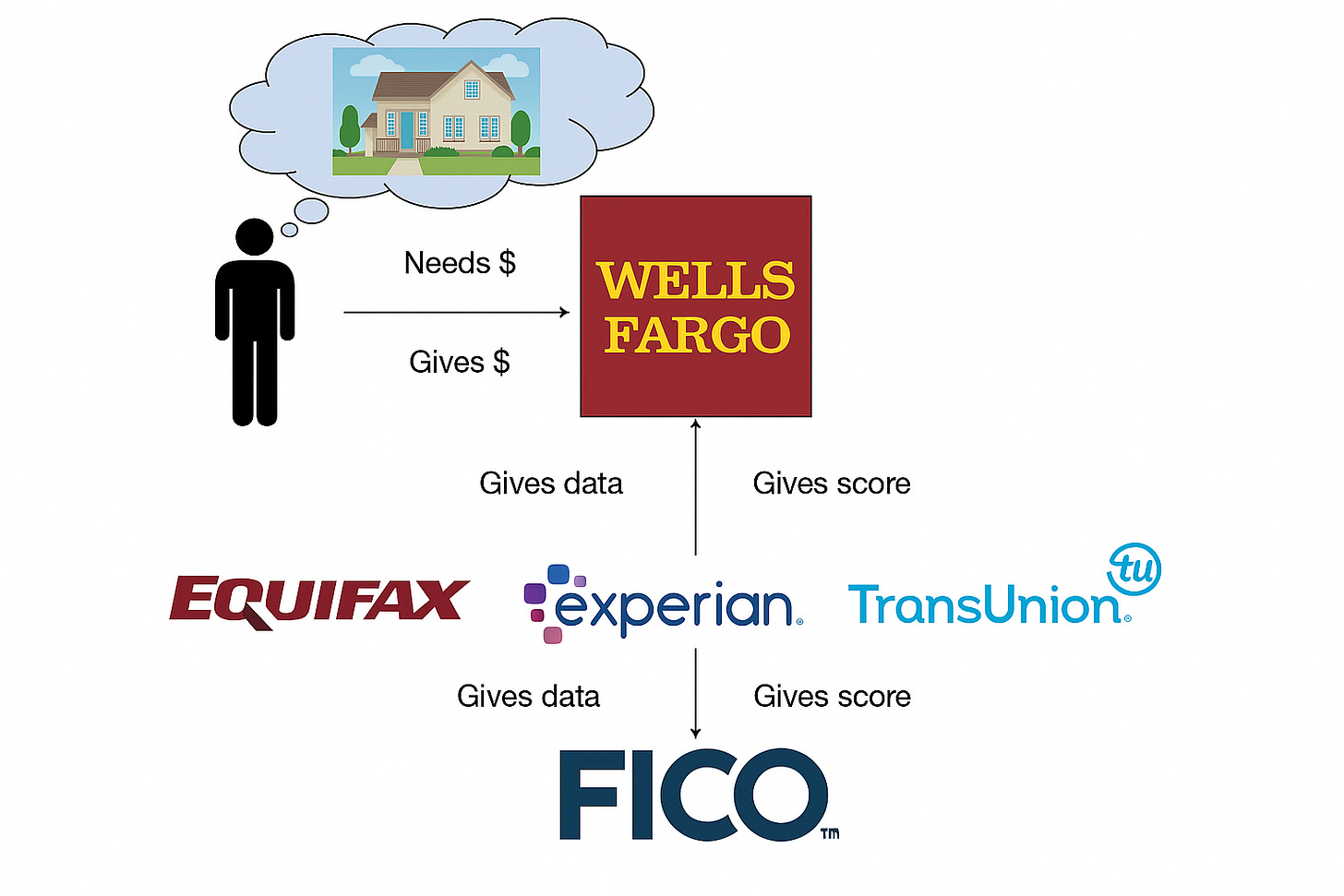

To give some more background, let’s talk about the value chain here.

Someone wants to buy a house, so they approach a bank. The bank needs a way to assess what kind of interest rate to give this person or if they should loan money at all. So the bank pulls a credit report and a FICO score. The credit report has more detail and is supplied by the credit bureaus, Experian, Equifax or Transunion. These bureaus were created to give banks and lenders a centralized database of consumers’ credit history.

Then FICO receives the credit bureau data, runs its algorithms and boom, a FICO score!

Here’s a visual representation of this process:

So banks give credit bureaus their data and then the bureaus give FICO their data. Then FICO aggregates that data into a score and gives it back to the bureau, which sells its reports alongside the FICO score back to the bank or lender.

Understanding the value chain here is important for understanding the moat. When learning about this, the first question I had was “Why can’t the bureaus just make their own scores?”

Well, they have. It’s called VantageScore. The big three bureaus created this FICO competitor, but it turns out, the adoption still isn’t nearly as high as FICO’s score. So clearly there is something special about FICO’s score, right? Well, sort of. The moat is primarily in the value chain.

VantageScore has some minor differences to FICO but it isn’t vastly inferior as a product. The adoption problem lies in the fact that FICO is such a trusted brand and that it is already in the workflow of all the top banks. Imagine you’re a loan officer for a bank and you’ve been trained to ask for credit reports and FICO scores. You’ve done thousands of loans with these two tools. Now, VantageScore pops up. Will you switch? Probably not because the risk likely outweighs the reward. For you to switch, VantageScore must be vastly superior since all of your risk models are based on FICO.

This dynamic also partly answers the question “Why don’t the bureaus just crank up the price on the data they sell to FICO?” However, there is more to this answer. Since FICO and the bureaus have a royalty agreement, if the bureaus raised the price, FICO would just raise the royalty. And since the banks are so comfortable with FICO scores, the bureaus are kind of stuck. The bureaus would actually rather FICO work directly with banks so that FICO wouldn’t have the royalty leverage. However, banks and lenders are creatures of habit. They wouldn’t prefer to work with two separate vendors. If the bureaus can somehow convince lenders to work with FICO directly, that would be interesting. Even still, FICO would probably cry collusion since the bureaus do have such a consolidated lock on the space. Nothing says “back off” like the possibility of an anti-trust lawsuit.

So you see, it’s not necessarily that FICO’s product is that much better. It’s that the industry structure is very unique. It’s pretty rare to have a supplier and a distributor (the bureaus) that doesn’t have maximum leverage in the value chain. The reason is that lenders are so used to FICO’s score within their workflow and risk models.

There is another piece to mention here as well. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, known as the GSEs (government sponsored enterprises) require FICO scores if a lender wants to sell a loan on the secondary markets. And more than 70% of mortgages are sold so it’s actually more than a preference thing – lenders must get a FICO score if they want to offload mortgages and juice their ROE. Further, this is why the bureaus don’t mind giving their anonymized data to FICO. It helps their business. Without FICO scores, the bureaus wouldn’t sell as many credit reports. So it’s actually mutually beneficial but FICO has realized their importance and therefore, flexed their pricing power. For 30 years, the bureaus kept FICO scores at a very low price, roughly 50 cents per credit report. Now, a mortgage origination costs a bureau a royalty of about $5 for a FICO score. The first time pricing went up was in 2018 so over the past 7 years, FICO has flexed pricing power by an order of magnitude, 10x, or almost 40% per year. This is why FICO is known as having incredible pricing power among sophisticated investors. In fiscal year 2022, the CEO, Will Lansing, noted that FICO mortgage scores cost $2-8, which at the high end is roughly $2.66/report. More recently, in November, that price went to $4.95, which is an 86% increase in 2 years. Essentially, the pricing has gone like this per report: 2023: $2.50 → 2024: $3.50 → 2025: $4.95

Right now, it costs roughly $100 for a lender to pull the three credit reports from the bureaus for a mortgage origination. And so FICO accounts for about 15% of that ($5 x 3 credit reports). As a percentage of the average closing costs ($6,000), that’s roughly 0.25%. So that’s why FICO has pricing power. It’s required by the GSEs but it’s a very small burden on the end consumer, the borrower. Typically, the lenders will bundle this small cost into closing costs. However, if the borrower gets rejected, the lenders are typically on the hook for these costs. That’s why lenders will often do a soft pull with one credit bureau to prequalify a borrower.

I’m frankly not quite sure what FICO could push pricing to. If it was 1% of closing costs, that’s still 4x latent potential. Or would 50% of the credit pull be reasonable? If so, that would be roughly 3x potential. You can play around with the numbers but a large component of it comes down to the GSEs requirement of FICO for selling mortgages. One very interesting thing relating to this is that the GSEs approved the VantageScore 4.0 as a verification for selling mortgages in 2022. However, the implementation of this is taking years and FICO is still the only game in town. The estimated timeline is late 2026 for lenders to start using Vantage as part of their process and this could shift the market power dynamics, thereby putting a damper on FICO’s pricing power. As part of this legislation, lenders will only need to pull two reports rather than the typical tri-merge. This would limit FICO’s royalty revenue as well since it would only get $10 instead of $15. These are two developments to watch very closely, especially since the GSEs might get privatized under Trump. This is important since the “Scores” business is the crown jewel, with 80%+ EBIT margins, and mortgage originations account for roughly 40% of the “Scores”.

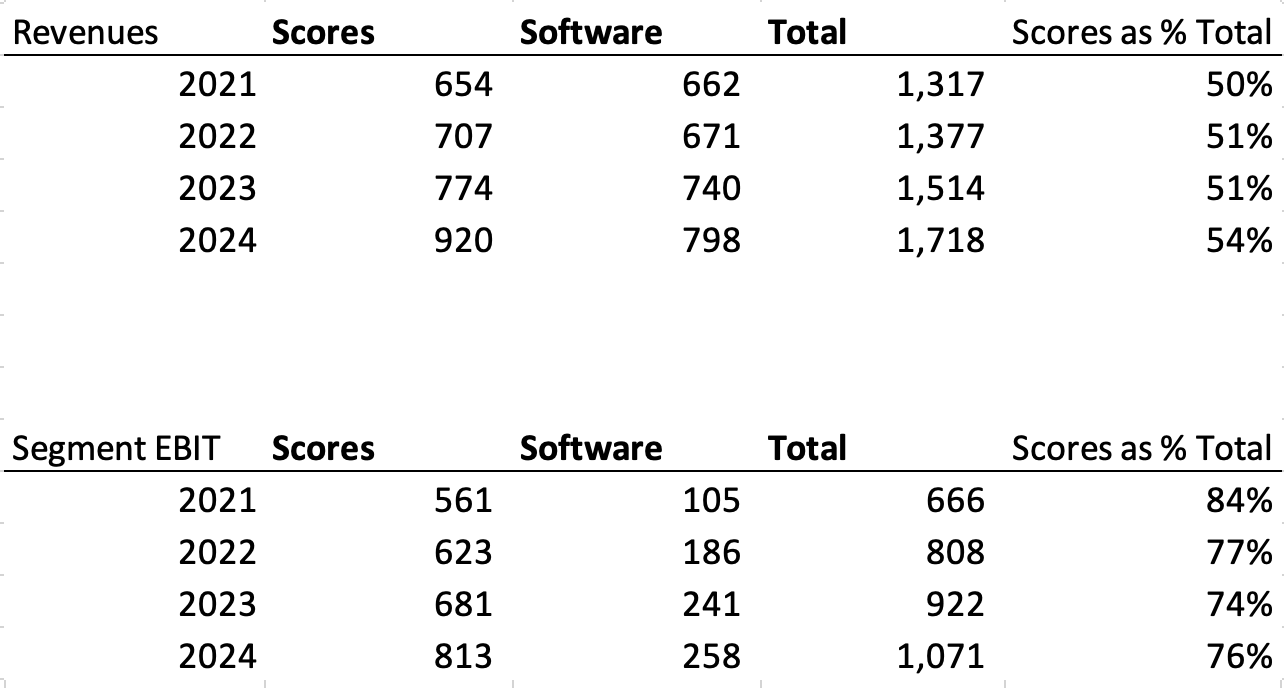

Besides the potent pricing power, FICO’s growth comes from credit growth. More mortgages, more car loans, and more credit cards mean more credit checks, which banks pay for on a transactional basis. That means FICO depends on the growth of the economy to a great extent. If no one is buying anything, no one is loaning money, and no one needs credit scores. So the fact that FICO has been able to flex its pricing power in a rising rate environment puts pressure on lenders. If rates do go down, FICO will grow from more volumes and more overall originations. I’ve been talking about the “Scores” business so much because that is truly where the profitability comes from. If you look at the segment operating income margins, the Scores make up 54% of revenue but over 75% of total operating income but it actually could be even higher as we don’t fully know the SG&A break out between Scores and the software business.

Business’ Economics

The company used to have three revenue segments but it is consolidated to two, Scores and Software.

Here are how the segments break down:

The most interesting thing though is how profitable the “Scores” business is.

Last year it did 88% segment EBIT margin. 88%! That’s the highest I’ve ever seen and it’s a testament to the industry dynamics. Since most of the COGS are just data and the bureaus can’t charge too high of a price, a ton of that revenue flows to the bottom line.

Overall, fully allocated EBIT margins come out to around 43%. Without the Scores business, FICO wouldn’t be nearly as attractive! With FICO, it’s all about scores. In 2018, they finally got approval to start raising Score prices. It’s not a coincidence that EBIT margins since then have more than doubled, from 19% to 43%. Pure pricing power is pretty much unlimited incremental return on capital as well. It doesn’t take a whole lot of capital to say, “Ok, TransUnion, your royalty rate is going up $1 next year.” Since 2018, EBIT has grown $560 million. During the same period, invested capital grew $290 million. Quite the incremental returns! This is why the stock always seems to trade at a nosebleed valuation. With huge pricing power, ROIC is off the charts so you can pay a pretty penny and it still can make sense. However, it will be important to watch the GSEs and if the VantageScore does make some progress under changing regulations. It seems likely that the corporate inertia from lenders will make this process extremely slow, favoring FICO, but it's more about how it affects future pricing power. I don’t fear for FICO’s market share necessarily, just the presence of a viable alternative that limits the market power of the company.

If you enjoyed this, please turn that ♡ into a ♥️. This will help others find this newsletter. Thank you so much 😁

As an aside, I’ll be in Omaha for the Berkshire meeting from Thursday-Sunday. Feel free to reach out if you’re going to be there.