As part of making Business Breakdowns free, we’re rolling out our formerly paid articles so subscribe if you’d like to get hit with an avalanche of free business analysis!

Visa is a tollbooth on commerce. But rather than connecting two cities, it connects two banks. And rather than cars, Visa transports data.

Visa is not a credit card company. It doesn’t issue credit cards, nor does it make any money from late fees or interest.

So how does it make money?

Before getting into that, let’s actually understand all the parties involved in a credit card transaction.

There are five main parties:

Account holders (that’s you buying stuff)

Issuing bank (that’s your bank)

Card Network (that’s Visa, Mastercard, etc.)

Merchant (the place you buy stuff)

Acquiring Bank (aka Merchant bank)

So the whole process looks like this:

You might be thinking, “Whoa, whoa, woah! That’s too many lines and words!”

And you’d be 100% correct. So let’s start at the beginning…

Here’s you (account holder) buying coffee at Starbucks (merchant).

Ok, easy enough right? But what happens when you swipe your credit card?

Well, keep in mind, that everything in the picture below takes place in about 3 seconds. So you swipe your card and that information travels from the card reader to the merchant’s bank which utilizes Visa’s electronic network to ask the issuing bank if you, the account holder, are even allowed to purchase the item. This process is called authorization.

With a debit card, the issuing bank is searching for whether you have sufficient funds. If your card has ever been declined and you needed to put more money on it, that’s what was happening behind the scenes.

With a credit card, this search is mainly looking for fraudulent activity since you don’t need the money in your account right away.

So here you can see that Visa is the connector between the acquiring bank and the issuing bank. To use the metaphor from the beginning, if these two banks were cities, Visa would be the road connecting them, taking a tiny piece of the transaction volume.

Now the transaction is approved. Authorization complete.

From here, at the end of the business day, the merchant will send the authorizations to its bank in a process called clearing.

Then the acquiring bank will, via the card network, ask for the money from the issuing bank. Once the acquirer receives the money, it pays the merchant subtracting a merchant discount fee (usually in the ballpark from 2.5-4%). This is called settlement.

So now we’ve covered authorization (making sure the account is good), clearing (sending the authorizations to the acquirer), and then settlement (where the issuing bank pays the merchant bank so it can pay the merchant).

After this, the merchant bank pays the issuing bank something called an interchange fee, which makes up the majority of the merchant discount fee. This makes sense because the issuing bank is on the hook for the debt. Since it is taking the credit risk, it deserves the largest piece of the fee.

And then, of course, the account holder has to pay back the issuing bank or else he/she will drown in credit card debt. Now the craziness of credit card interest makes more sense because these banks are on the hook for billions of transactions. They need to be compensated for it.

So there we have it. More than you’d ever like to know about the nitty-gritty details of the payment system. And we haven’t even touched on web gateways, payment processors that aren’t acquirers, and ISOs! We’ll leave that for another time 😜

And all the while, Visa is sitting there connecting the banks, taking a very small amount of the transaction volume, called an assessment.

Just how small?

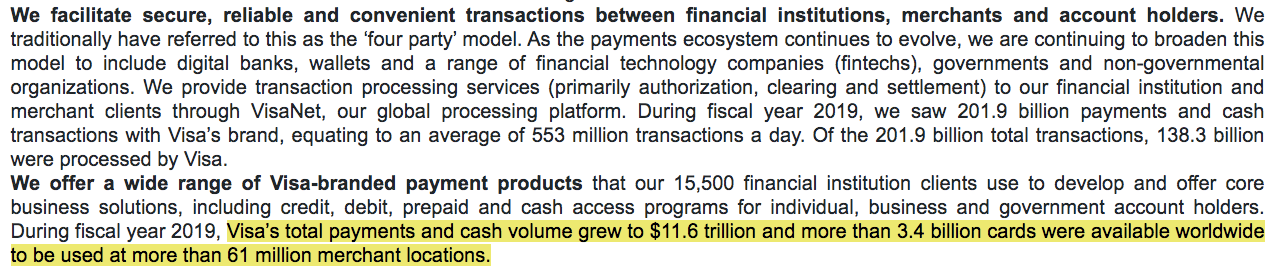

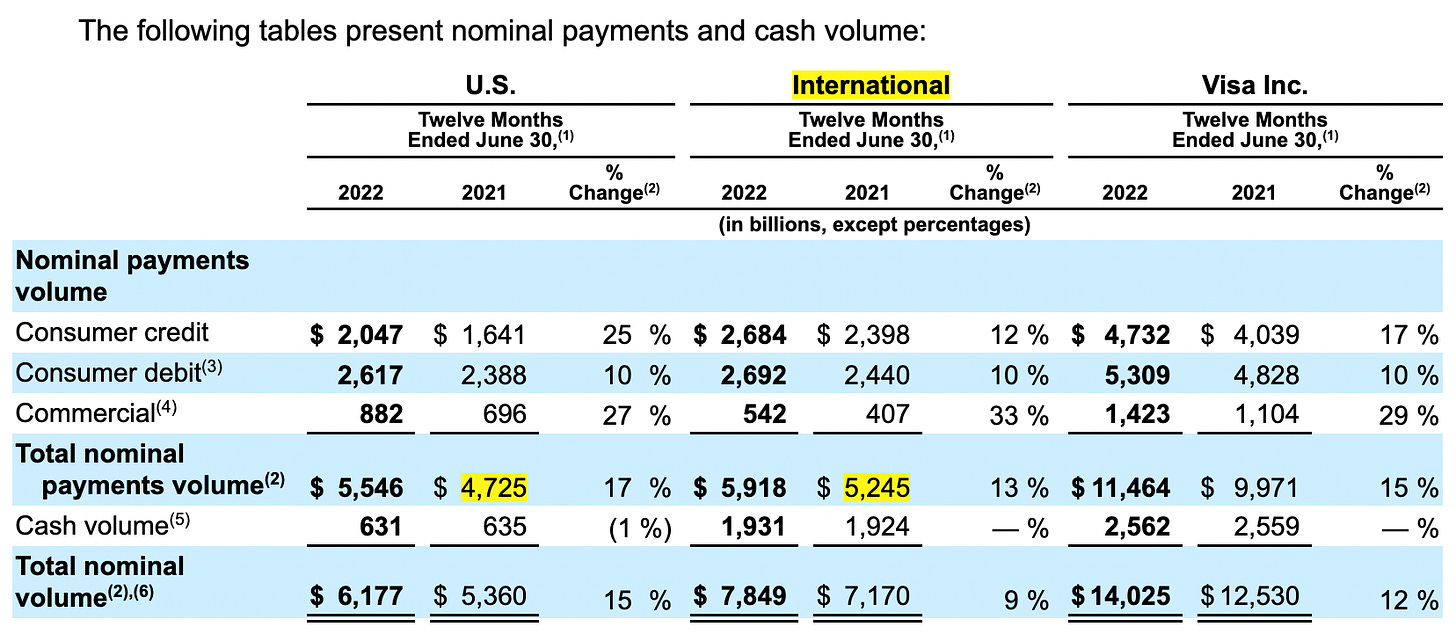

Well in 2019, $11.6 trillion, yes that’s trillion with a t, went through Visa’s network. And of that, the company “only” did about $23 billion in revenue. Most recently, the company did $29 billion on $14 trillion in volume, which also comes out to 0.20%.

So out of that 2.5-4%, Visa only takes less than 1/10th of it or 0.2% of the whole payment.

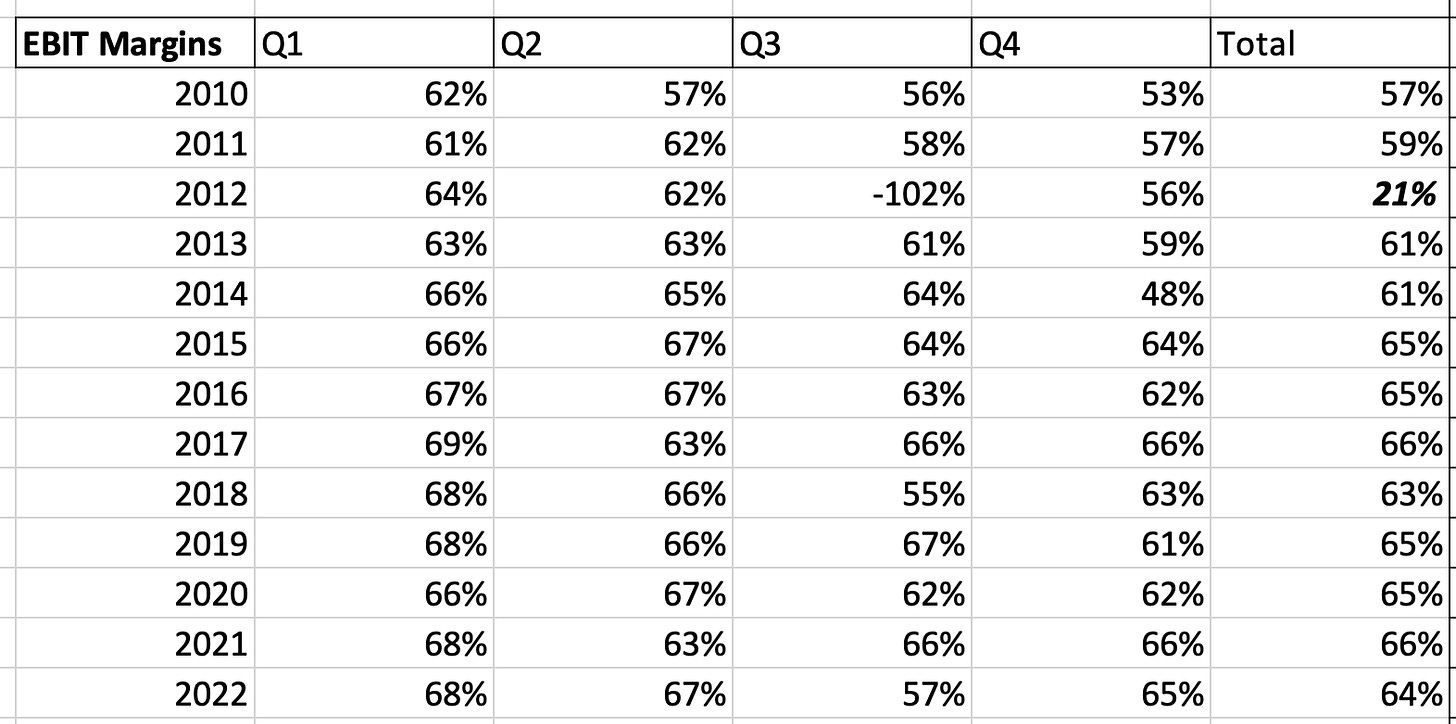

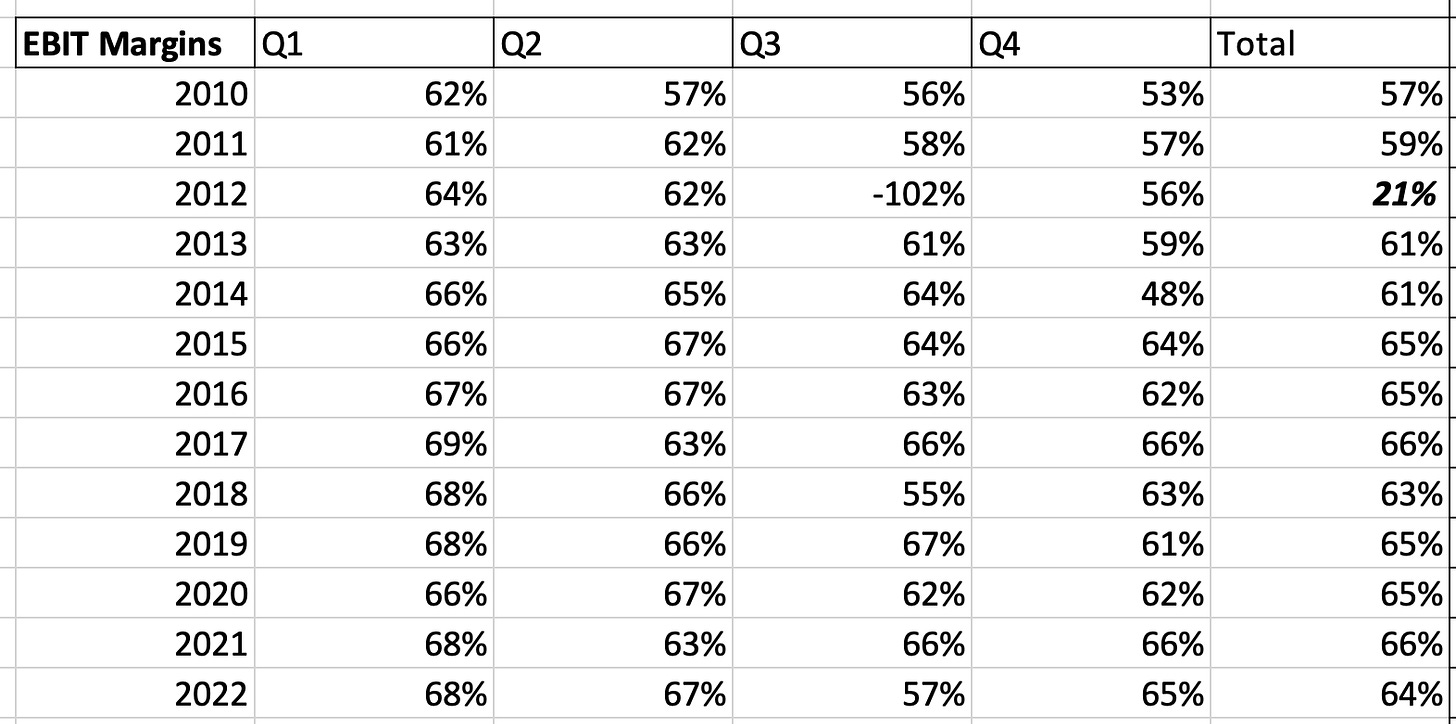

That means if you buy Airpod Pros for $250, Visa will usually take 50 cents. So it’s a very small amount. Just like a tollbooth, Visa is sitting there, connecting banks so that we can use credit cards to our heart’s delight. They are literally more a digital database moving around bits of information than anything else. That’s why the margins are so high. I mean, for goodness sakes, look at these!

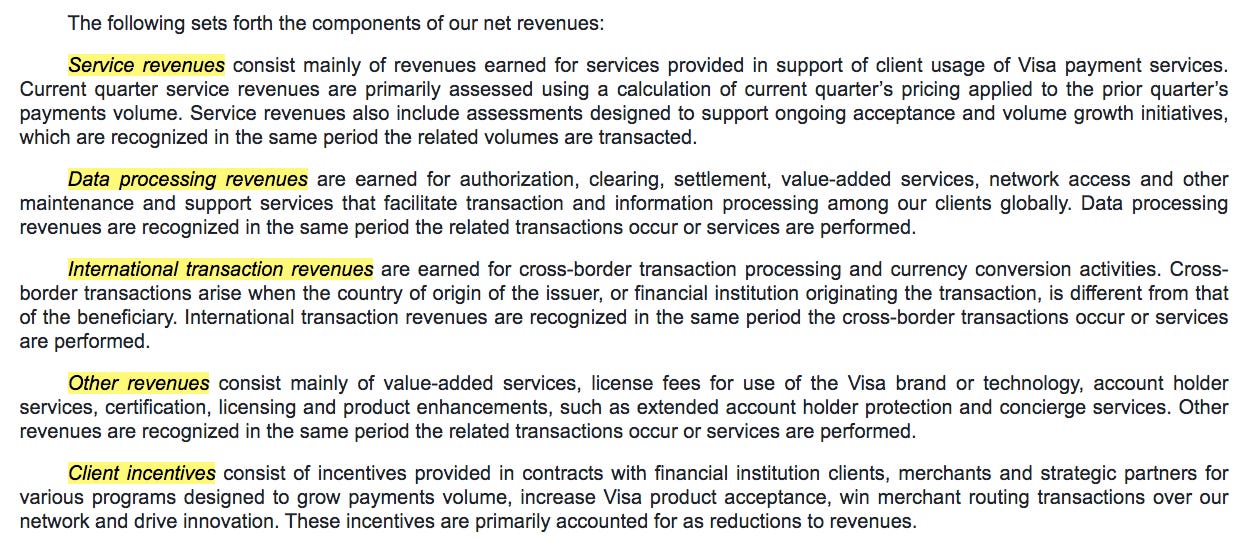

Now that we understand the background of where Visa sits, let’s dive into its own specific revenue segments.

The five are:

Services

Data processing

International Transaction

Other

Client Incentives (contra-revenue)

The main three segments are services, data processing and international.

As we can see, international is a sizable part of the business. In fact, the company does more revenue internationally than domestically. International revenue is recognized when the issuing bank and the other financial institution are in different countries of origin.

What’s also interesting from this chart is that Visa processes more debit volume than credit.

Going back to the revenue segments, the difference between service revenue and data processing is that the latter involves processing the transaction. Processing is what we talked about with authorization, clearing and settlement. On top of this, Visa gets paid a service fee, almost like an access fee for the banks to use the network.

But what about the internet? How does Visa stay in the game?

Well, the internet doesn’t really change anything for the card networks. After all, banks still need to be connected. The internet really messes with the acquirers because companies like Adyen and Stripe act as merchant banks for online businesses. These players, sometimes known as web/payment gateways, still need Visa’s network.

What would be really interesting and probably anti-competitive is if these gateways created personal banking solutions as well. Imagine using Stripe to process your business’s online transactions and then withdrawing money into your Stripe checking account. In that case, Stripe wouldn’t need to use the card network rails since the money doesn’t need to be transported anywhere.

However, this won’t happen (at least not for a long, long time) because you still need to think about customers. They wouldn’t all have Stripe credit cards.

This is essentially what Alibaba has done in China with Alipay. Since so many people use Tmall and Taobao, (its online marketplaces) the company was able to leverage that into a money transfer system, bypassing the card networks altogether.

In the US, a potential culprit to pull this off could be Amazon, enabling it to move money inside its own walls for suppliers. But that wouldn’t affect off-line transactions wherein Visa has a formidable network effect. More realistically, Square’s vision (now Block) was to create a closed-loop payment network with its plethora of point-of-sale systems and its consumer-facing, Cash App. However, the card networks are still deeply ingrained in the payment ecosystem because of how strong the network effects are. So many banks issue Visa and Mastercard cards and virtually all merchants, both offline and online, accept those cards.

In this light, you can begin to see the moat of Visa and Mastercard; they charge such a small amount for how important of a function they fulfill. Even a company like Stripe which can aggregate a ton of demand is still beholden to Visa.

Some people may ask, well what about Bitcoin and decentralized networks?

Again, not for a long time.

The issue is scalability. Visa can process 5,000 transactions per second and Bitcoin can process anywhere between 4 and 7 per second. Sure, the scalability will improve but that compromises one of the main benefits of Bitcoin, which is security.

All in all, Visa’s capital-light business model allows it to re-invest capital at very high rates.

Let’s just bask again really quickly in the company’s EBIT margins. They are practically second to none.

The company is a tollbooth on the economy. It’s not a credit card company, it’s actually more like a data company. Its data centers electronically connect banks and Visa gets paid very small amounts in the process.

The company could surely flex its power and raise “prices” 10%. Even then, the take rate would be just 0.22%. However, the $4 billion fine in 2012 probably still leaves a mark. It’s a delicate balance because Visa and Mastercard own so much of the market. In the US, estimates put Visa’s market share at around 53% and Mastercard’s at about 22%. So these two companies own about 75% of the market.

These companies even set the interchange rates for the issuing banks. For instance, in Visa’s schedule, you will find that a Visa Signature credit card transaction for travel costs 2.25% + $0.10 vs. a travel debit transaction for a regulated issuer (above $10 billion in assets) is 0.05% + $0.21. In 2010, the Durbin Amendment limited the cost of a debit transaction to this particular cap (0.05% + $0.21) for regulated financial institutions. However, issuers with less than $10 billion could be reimbursed at higher rates so they could stay competitive and still make money.

So even though Visa is only getting paid out 0.2%, it has the power to set the rates for all of the issuing banks it works with. Why? Because it has the leverage, all of the disparate banks can’t communicate seamlessly with each other on a global scale without Visa.

With great pricing power also comes great responsibility since the card network’s decisions affect consumers. When the consumer is involved, politicians are quicker to regulate.

However, as the world continues to transition away from cash and to digital payments, Visa is a behemoth with a fantastic, capital-light business. Though people throw around a lot of risks, understanding the details allows us to see the card networks have a solid position.

Hi Ryan,

Thanks for this, very ueful.

How does the development of Account-to-Account transactions affect the networks? Do banks still need to be "connected" via a Network? Does PSD2 make this easier for them?

Insightful and thorough breakdown, Ryan! Incredible to consider that companies like Stripe, Brex, Divvy, and Galileo Financial Technologies all rely on MasterCard or Visa. I'd love to hear your thoughts on PayPal!